Crystal Arcade

The Crystal Arcade during its heyday. © Arquitectura Manila Photo File

The Philippine capital of Manila was a city of high stature, comparable to those fine cities of the Occident such as Paris, London, and Madrid. The pre-war years have given Manila to acclaim itself as the 'Most Beautiful City in the Far East' whilst Manila's neighbors, Hong Kong, Jakarta, Kuala Lumpur, and Singapore, were backwater outposts of their colonial masters. This is proven by the influx of European migrants and expatriates to the city in the first half of the 20th century. Germans, Spaniards, Americans, British, French, and Russians made Manila their home, at least, until the end of the Second World War. These migrants and expatriates mingled with the Philippine alta sociedad and had the city developed from a medieval Spanish city into a progressive capital of a semi-independent nation.

Shopping around the city is one of the best things to do in Manila. Long before the existence of modern Philippine shopping mall complexes such as Rustan's, Shoemart, Robinson's, and Ayala, the Crystal Arcade is considered the first shopping mall in the Philippines.

Façade of the Crystal Arcade. © Lougopal.com/Manila Nostalgia

The Crystal Arcade was one of the most modern buildings located along the Escolta, the country's then premier business district. Built on the land owned by the Pardo de Tavera family, an illustrious Filipino family of Spanish and Poruguese lineage, the modern building was designed by the great Andrés Luna de San Pedro, a scion of the latter. The Crystal Arcade was designed in the art deco style, a style prevalent in the 1920s to the 1940s. It was to be one of Luna's masterpieces, with the building finish resembled that of a gleaming crystal.

The conception of a construction of the Crystal Arcade started in the 1920s as a pet project of Luna. Luna wanted to have the same prestige in the arts and architecture like that of his father, the great revolutionary-painter Juan Luna Novicio. To make such thing possible, he infused the sleek and streamline art deco design with crytal-like glass in his design for the building.

Andrés Luna de San Pedro (1887-1952) © Lougopal.com/Manila Nostalgia

The Crystal Arcade was inaugurated in June of 1932, and was the first shopping establishment, or the first commercial establishment that was fully air-conditioned. Its interiors reminded the Philippine elite of the arcades that of Paris, with covered walkways, glass covered display windows and cafés and other specialty shops.

Crystal Arcade interior, adorned with a pair of grand staircases. © Manila Nostalgia/Carmelo Mosqueda

Inside the Crystal Arcade, one can find the home of the first Manila Stock Exchange, the precursor to today's Philippine Stock Exchange.

A typical trading day at the Manila Stock Exchange inside the Crystal Arcade.

According to sources, the Crystal Arcade was used to be owned by its architect, the great Andrés Luna de San Pedro, probably due to the land being owned by his maternal family, the Pardo de Taveras, but was foreclosed by its creditor, the El Hogar Filipino, due to the financial situation that came about during the Wall Street crash and the Great Depression in the late 1920s to the early 1930s. The Crystal Arcade was also planned to have more floors but was eventually scrapped because of lack of funds.

When the Crystal Arcade opened in 1932, it was the most elegant building in the area as it was constructed with glass which illuminates like crystal at night. Its interiors were also as elegant as the exterior, showing art deco lines and motifs.

"The Arcade had a mezzanine on both sides of a central gallery that ran through the length of the building and expanded at the center to form a spacious lobby containing curved stairways. Stairs, balconies, columns and skylight combined to create vertical and horizontal movement, as well as a play of light and shadow in the interior. Art deco bays pierced by a vertical window marked each end of the façade and complemented the tower over the central lobby. Wrought-iron grilles and stucco ornaments were in the art deco style featuring geometric forms, stylized foliage, and diagonal lines and motifs." (excerpt from Philippine Politics and Society in the Twentieth Century: Colonial legacies, post-colonial trajectories)

Escolta in 1937. The Crystal Arcade is on the left of the photo. © Lougopal.com/Manila Nostalgia

In 1941, the Second World War came to the Philippines only hours after Pearl Harbor was bombed. The capital city, Manila, was also bombed by the invading Japanese forces causing damage to the city. The following year, in January, triumphant Japanese forces entered the city despite of it being declared an open city. During the occupation years, the Crystal Arcade was home to Japanese occupation agencies such as the Japanese Government Railways and the Board of Tourist Industry.

The year 1945, for those who lived in Japanese-occupied Manila, was probably the most traumatic and devastating year. In the months of February and March saw the most bitter fighting in all of the Pacific. Sixteen thousand (16,000) fanatical Imperial Japanese Navy soldiers fought American and Filipino forces to the last man, bringing with them about one hundred thousand (100,000) civilians massacred. The effect of this bitter fighting resulted in the near-total destruction of the City of Manila. More than eighty (80) percent of the city's structures were obliterated, many of them into extinction. The Crystal Arcade, located along the Escolta, was one of the casualties of war, Escolta being one of the areas of fierce combat.

A heavily damaged Crystal Arcade taken immediately after the liberation for Manila. © George Mountz Collection

Shelled-out interiors of the Crystal Arcade. © Lougopal.com/Manila Nostalgia

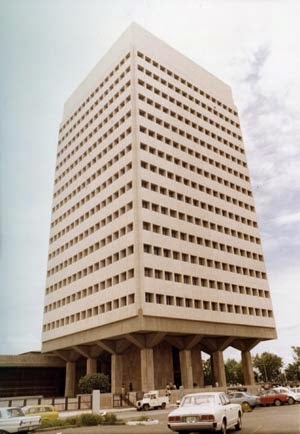

Immediately after the liberation of Manila, businesses soon opened even its locations were in shambles. In the Crystal Arcade, businesses reopened and some new businesses found a home in the Crystal Arcade. Only the first floor was occupied with stores and the second floor being a bodega, or storage room of the tenants. Eventually, in the 1960s, the Crystal Arcade was demolished to pave way for the post-war revival of the Escolta. Its successor, the new Philippine National Bank Building, designed by Carlos Argüelles, replaced the Crystal Arcade, the Lyric Theater, and the Brias Roxas Building.

Heacock's Department Store

A typical scene outside Heacock's Department Store along the Escolta. © Manila Nostalgia/John Harper

Long before the existence of today's department stores such as Rustan's, Robinson's, and the ever-famous Shoemart, now known as SM, there were already department stores that were far more luxurious than that of today's. Manila, being the city that boasted numerous feats in architecture, also hosted and boasted the finest shops and stores in all of the Orient. One of these department stores was Heacock's, probably the most recognized and popular stores in the city back in the day.

Heacock's Department Store first became a jewelry store operating under the partnership name Heacock & Freer, two American brothers-in-law from San Francisco. H.E. Heacock, one of the partners, was a travelling salesman originally hailed from Salem, Ohio and first came to the Philippines in 1901 to open a branch of his jewelry store. After arriving in Manila, Heacock & Co. set up shop on the second floor of the McCullough Building at the foot of the Santa Cruz Bridge. Since then, Heacock & Co. became the best known American jewelry store in the city.

H.E. Heacock, one of the founders of H.E. Heacock & Company. © Filipinas Heritage Library

In 1909, the brothers-in-law Heacock and Freer sold the company to Samuel Francis Gaches, a young American entrepreneur-turned-philanthropist who arrived in Manila in the same year as Heacock, but the reason being is that Gaches worked for the American colonial civil service.

Samuel Francis Gaches, president of the H.E. Heacock & Company. © Filipinas Heritage Library

In the post-Gaches acquisition of the company, the year 1910, H.E. Heacock & Co. transferred its operations south, at an old building along the five-block Escolta. The old Escolta shop was renovated and had the most modern storefront in all of Manila with its products displayed in front, a first in the country. Eight years later, in 1918, Heacock's transferred its operations again due to the success of the department store. It moved one block east, along the Escolta corner Calle David. The new four-storey Heacock's Department Store was the most modern of its time. The department store was built on the lot of American businessman William J. Burke, the owner of the Burke Building on the Escolta.

The pre-1918 Heacock's Department Store along the Escolta. © Manila Nostalgia/Isidra Reyes

As the years progress, Heacock's grew larger in terms of popularity and in assets. The H.E. Heacock & Company opened branches in other parts of the Philippines such as in Baguio, Cebu, Davao, and Iloilo. Heacock's, being the country's largest department store back in the day, carried imported luxury goods from the Elgin Watch Company, which carried the brands Lord Elgin, Lady Elgin, and Elgin. Other brands include Remington Typewriters, Rogers Flatware, International Silver, and Frigidaire Refrigerators.

An ad from the Philippines Free Press dated December 1923 from Heacock's Department Store. © Manila Nostalgia/Aksyon Radio La Unión

The year 1929 saw the birth of a stronger and larger Heacock's Department Store. Gaches and the H.E. Heacock & Company started the construction of the one million peso (P1,000,000.00), eight-storey Federal style building on the corner of Calle Escolta and Calle David. The new Heacock Building was designed and constructed by the triumvirate of the Filipino architect Tomás Argüelles, the American W. James Odom, and the Spanish Insular Fernando de la Cantera. Opened a year later, the Heacock Building had the same features that of the old Insular Life Building at Plaza Moraga.

Construction of the new Heacock Building in 1929. © Lougopal.com/Manila Nostalgia

In an article of the American Chamber of Commerce Journal in 1930, the new million-peso Heacock Building was described as being one of the tallest in the city. The article also described the interior layout of the department store.

"The main entrance on the Escolta opens into Heacock’s proper, the jewelry store; then comes Denniston’s, the photographic department, with its valuable Eastman agency, and then the office equipment department. The jewelry store is L-shaped; one of the illustrations gives a good view of it.

In the new building the Heacock store occupies the main and mezzanine floors, both handsomely finished and artistically arranged. The second floor is also all occupied by the Heacock company; the offices are there, and the stock, accounting, mail order, wholesale and optical departments. Four rooms on the third floor are given over to stock and records; the other rooms of that floor are rented as offices, as are the rooms and suites of the fourth, fifth and sixth floors. These rooms, all of them desirable because of their location and the building they are in, offer great latitude of choice.

The seventh floor accommodates Heacock’s engraving and printing, watch-making, metal engraving, jewelry repairing and manufacturing departments; also the optical shop, Denniston’s photo laboratories, and stock of the office equipment department.

The basement, under the entire building, counts as the eighth floor. It is to accommodate automobiles during the day. Seventy-five cars will not crowd it; a wide ramp opens from Calle David, egress and ingress are safe and convenient. This public service in connection with the Heacock building will materially mitigate the downtown parking nuisance." (excerpt from the American Chamber of Commerce Journal)

The new million-peso, eight-storey Heacock Building. © Manila Nostalgia/Isidra Reyes (Retrieved from Arquitectura Manila Photo File)

Interior of the Heacock Building on its opening in 1930. © Lougopal.com/Manila Nostalgia

The triumvirate-designed edifice only lasted for seven years. In 1937, a powerful earthquake hit the Philippine capital which heavily damaged the Heacock Building. The building suffered irreparable damages which led to the demolition of the eight-storey building. Heacock's shut down its business and was quickly reorganized a month after the earthquake.

The new edifice, also eight stories high, replaced the old demolished Heacock Building. The new building, built in the streamline art deco style, was designed also by Tomás Argüelles, but with Fernando H. Ocampo and the American George E. Koster.

The new H.E. Heacock & Company Building in 1940. © Manila Nostalgia/Dominic Galicia

The streamline art deco building had the latest in building technology, it had installed pneumatic tubes which could transport small parcels throughout the building without the need of a messenger. The building cost around P800,000.00, which is P200,000.00 cheaper than the triumvirate-designed Federal style building.

The new H.E. Heacock Building (center) houses Heacock's Department Store and the ammunition storage of the Philippine Army. © LIFE via Lougopal.com/Manila Nostalgia

The deadly Battle of Manila in 1945 greatly reduced the city into rubble. Escolta, home of the city's financial district, was obliterated by bombshells and gunfires. The Heacock Building was damaged but was reconstructed after the war.

The war-torn H.E. Heacock Building, 1945. © Skyscrapercity.com

Michel Apartments

The Michel Apartments at its splendor. Ⓒ Manila Nostalgia/Isidra Reyes

Long before the rise of multi-storey residential apartments in post-war Manila such as in Makati, there were already numerous apartments that were as elegant, if not, more elegant, than those of today's, in pre-war Manila. Manila, being the capital of a prosperous Philippine Islands, was once home to many expatriates of different nationalities, such as Spanish, American, British, and German. And within the confines of the modern residential section of Ermita and Malate lies the Michel Apartments, one of the city's top residential apartment.

The Michel Apartments was an art-deco, mid-rise apartment building designed by Francis 'Cheri' Mandelbaum, whose other work was the Rosaria Apartments nearby. Mandelbaum was an American architect trained in Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. He also spent some time in the Philippines, coming to the islands in 1904 to work in the Bureau of Public Works with William Parsons, urban planner and architect of the Paco Station of the Philippine National Railways. Also, he worked as a professor of architecture at the University of Santo Tomás in Manila.

At some time, the Michel Apartments was the tallest apartment building in the City of Manila.

The Michel Apartments lay in ruins after the liberation of the city in 1945. © Manila Nostalgia/Isidra Reyes

The Michel Apartments stand nine storeys high on a 1730-square meter lot along Calle A. Mabini in Malate, the residential section of the city where many of the country's pillars in social, economic, and political institutions resided. The Michel was commissioned by Don Pedro Sy-Quia y Encarnacion, a scion of the old and landed Sy-Quia family from the north. The Michel was said to be named after his wife, Doña Asuncion Michels de Champourcin y Ventura, a mestizo from Pampanga.

This year, 2014, the Michel Apartments was hounded with a demolition permit, despite of it being a protected structure under law. The demolition of the Michel Apartments was stopped by heritage conservation activists and citizens alike through the "cease-and-desist order" from the court. But, the demolition of the Michel had already started when the court ruling came out, so it would be of no use.

Destruction of heritage structures should be given the highest priority, as physical heritage is rapidly declining because of irresponsible governance of local leaders. If the government continues to act in a way like they do not give importance to the country's heritage, then these structures will be prey to money-hungry developers.

The Michel Apartments was an art-deco, mid-rise apartment building designed by Francis 'Cheri' Mandelbaum, whose other work was the Rosaria Apartments nearby. Mandelbaum was an American architect trained in Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. He also spent some time in the Philippines, coming to the islands in 1904 to work in the Bureau of Public Works with William Parsons, urban planner and architect of the Paco Station of the Philippine National Railways. Also, he worked as a professor of architecture at the University of Santo Tomás in Manila.

At some time, the Michel Apartments was the tallest apartment building in the City of Manila.

The Michel Apartments lay in ruins after the liberation of the city in 1945. © Manila Nostalgia/Isidra Reyes

The Michel Apartments stand nine storeys high on a 1730-square meter lot along Calle A. Mabini in Malate, the residential section of the city where many of the country's pillars in social, economic, and political institutions resided. The Michel was commissioned by Don Pedro Sy-Quia y Encarnacion, a scion of the old and landed Sy-Quia family from the north. The Michel was said to be named after his wife, Doña Asuncion Michels de Champourcin y Ventura, a mestizo from Pampanga.

This year, 2014, the Michel Apartments was hounded with a demolition permit, despite of it being a protected structure under law. The demolition of the Michel Apartments was stopped by heritage conservation activists and citizens alike through the "cease-and-desist order" from the court. But, the demolition of the Michel had already started when the court ruling came out, so it would be of no use.

Destruction of heritage structures should be given the highest priority, as physical heritage is rapidly declining because of irresponsible governance of local leaders. If the government continues to act in a way like they do not give importance to the country's heritage, then these structures will be prey to money-hungry developers.

Admiral Apartments

The Admiral Apartments back in the day, photo probably taken after the war. Ⓒ Manila Nostalgia/John Harper

The grandeur of pre-war Manila makes people of today reminisce about the past, the past that has been prosperous and plentiful. Manila, being the finest city in the Orient proves its stately grandeur through the representation of the city's finest homes, shops, and imposing structures. Sadly, many of the structures that Manila boasts and had boasted is now being turned into fine pieces of powder as they are being demolished to pave way for the so-called "progress".

Along the scenic Dewey Boulevard, where the pride of the City of Manila, the Manila Bay, is located, there were numerous stately homes and apartments that stood in front of its glowing waters. One of them is the Admiral, located at the corner of Dewey Boulevard and Cortabitarte. The Admiral Apartments had been home to numerous historical figures, both local and global, and had been a witness to the gruesome days of the Second World War.

Admiral Apartments during the post-war years. © Manila Nostalgia/Isidra Reyes

The Admiral Apartments along Dewey Boulevard, now Róxas Boulevard, was a work of the eminent Fernando H. Ocampo, whose other works include the Calvo Building along Escolta, Angela Apartments in Malate, and the post-war rehabilitation of the Manila Cathedral. Built in 1938 and completed in 1939, the Admiral Apartments was commissioned by Don Salvador Araneta Zaragoza and his spouse, Doña Victoria López de Araneta.

Salvador Araneta Zaragoza and Doña Victoria López de Araneta.

The Admiral Apartments, after its opening in the late 1930s, was one of the tallest residential building in the city, with eight storeys high living quarters. Because of its height, the Admiral became the focal point of sailors and ships anchoring in Manila Bay.

Modern-day Admiral Apartments-turned hotel. Ⓒ Manila Nostalgia/Isidra Reyes

According to Manila society legends, the Admiral was conceived by Doña Victoria's mother, Doña Ana López Ledesma. It was said that Doña Ana was responsible for financing the construction of the Admiral to please and impress the Aranetas, specifically Don Salvador's father Don Gregorio Araneta Soriano, because it has been told that Don Salvador had married Doña Victoria without their knowledge.

The Admiral was designed in the art-deco style, designed by the eminent Fernando H. Ocampo. According to an architectural historian, he described the Admiral of having "an air of quiet elegance with definite Spanish touches in the design of its façade. The apartments were pleasant spacious, airy, and bright rooms. The Spanish feeling became more pronounced in the reception room that opened directly to a side street. Both the furniture and the metal chandeliers reflected a Spanish Gothic style, rather forbidding in its formality." (excerpts from a PowerPoint presentation by Isidra Reyes. Retrieved from Manila Nostalgia)

The features of the Admiral's interiors, such as the main dining halls, were designed with different themes and motifs. "The main dining room, called the Malayan Court, was so-called due to the strong Malayan motif of its design and an imposing mural painting by Antonio Dumlao. The Spanish Room was a reception room while a small dining room called the Blue Room was done in royal blue, old rose, crystal, and silver. A cocktail lounge called the Coconut Grove was decorated with a coconut trees with green light bulbs as fruits, inspired by the Cocoanut Grove Nightclub at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles." (excerpts from a PowerPoint presentation by Isidra Reyes. Retrieved from Manila Nostalgia)

During the war, the couple's own home, the Victoneta I, was seized by the Japanese and made it their headquarters. So, the couple and their family moved to the Admiral to seek refuge, along with other members of the López-Araneta families. It has been said that Doña Victoria personally did the washing of the dirty linens and taking phone calls as the Admiral Apartments was understaffed. In the last days of the war, the Japanese took control of the Admiral Apartments. With that, the Araneta couple moved out of the Admiral and sought refuge in Baguio along with other members of the López-Araneta family.

The Admiral Apartments (top center), during the liberation of Manila in 1945.Ⓒ Manila Nostalgia/Andi Desideri

The battle for the liberation of the City of Manila left most of the city in ruins. The Admiral Apartments was not severely damaged in the fight for the recapture of the Philippine capital. Shortly before the capitulation of the Japanese forces in the Philippines, top commanders of Allied nations in the Pacific stayed in the Admiral Apartments. The Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces in the Pacific and Field Marshal of the Philippine Army Douglas MacArthur has made the Admiral his temporary home after his home in nearby Manila Hotel was bombed out during the liberation. The British supreme commander, The Earl Mountbatten of Burma, formerly Prince Louis of Battenberg, uncle of Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, also stayed in the Admiral Apartments.

Construction workers demolish the Admiral Apartments. Ⓒ GMA News/Danny Pata

This year, in 2014, news regarding the Admiral Apartments sparked when it was reported that it is being demolished to pave way for a new development, the Admiral Hotel by Anchor Land Holdings. Petitions have been made throughout social media by heritage conservation activists and ordinary citizens alike, saying that the capital city of Manila has already had too much "massacre" of heritage buildings. The petition for the stopping of the demolition had reached the Manila City Hall, but took a blind eye on the issue. So, the developer, Anchor Land Holdings, continued the demolition, much to the disappointment and frustrations of heritage conservationists.

The year 2014 has already been a roller-coaster ride for Philippine heritage. No concrete plans and actions have been laid out by the government for the protection of heritage structures. As long as there are no concrete and stricter laws regarding the destruction of heritage structures, they will fall prey to greedy developers whose aim is to destroy the country's physical heritage.

De La Salle University St. La Salle Hall

The St. La Salle Hall of the De La Salle University during its heyday. © Manila Nostalgia/Gilbert Jose

Many have either walked past by this building or have walked through its halls. This outstanding structure is the epitome of institutional architecture in the Philippines, mainly because of its classical ornaments such as its white-washed walls and spacious halls. The St. La Salle Hall embodies the spirit of not just of the green and white, but also embodies the triumph of Catholic education in the Philippines.

Lasallian education in the Philippines was established in 1910 when the pioneer brothers arrived. It was not until in 1911 when the Brothers opened a school, which was then called the De La Salle College, at the Pérez Samanillo compound in Calle Nozaleda in Paco. Ten years later, as the student population began to increase and due to the lack of space, the De La Salle College moved to a much wider lot in the southwestern part of the city, along Taft Avenue in Malate.

A competition for the design of the new school building was initiated by the Lasallian brothers. Tomás Mapúa, a pensionado architect, won the competition against nine other entries and was awarded with a prize of P5,000.00. Mapúa is the country's first registered architect who was one of the first-generation pensionado architects who studied abroad. Educated in Cornell University in New York, he became one of the country's leading architects during the pre-war years, with projects such as the De La Salle University's St. La Salle Hall and the Philippine General Hospital.

The cornerstone for the new school building was laid by the Archbishop of Manila, the Most Reverend Michael J. O'Doherty, in March of 1920. The St. La Salle Hall was completed almost four years after, owing to the phase-by-phase construction because of the Brothers' lack of funds. The new school building was officially opened in December 1924.

St. La Salle Hall in the 1930s. © Easyphil.com

According to an article by Arch. Augusto Villalon on the Philippine Daily Inquirer, the St. La Salle Hall is the only Philippine structure to be included in the coffee-table book 1001 Buildings You Must See Before You Die: The World's Architectural Masterpieces. Denna Jones, one of the book's contributors, Denna Jones, have written about the St. La Salle Hall as an epitome of classical and imperial style of architecture not just in the Philippines but also in Southeast Asia.

"Mapúa's H-shaped, three-story reinforced concrete building is pure Classical expression. A triangular pediment crowns an entablature of cornice, frieze and architrave supported by Corinthian columns to create a three-bay portico main entrance."

"Wide, open-air portico wings extend from either side; the square openings on the third floor balanced over the rectangular openings of the upper floors? balustrade level. Corinthian pilasters and a dentiled cornice unite the floors between each arch."

"The interior quadrangle is similarly ordered but stripped to basic flat elements without benefit of pediment and entablature. A later addition of an exterior green metal slope-roof walkway wraps the ground level on the quadrangle side. The ground floor interior offsets Corinthian grandeur with the geometric simplicity of Tuscan columns, and a square coffered ceiling." (excerpt from Inquirer.net, original text by Denna Jones)

The Chapel of the Most Blessed Sacrament. © Manila Nostalgia/Isidra Reyes

In 1939, an addition was made to the St. La Salle Hall. Mapúa added a chapel on the western-most side of the building. After its completion, it was named as the Chapel of the Most Blessed Sacrament and was dedicated to St. Joseph.

The years 1941 to 1945 were bitter years for the Philippines. The country was unexpectedly and forcibly dragged into war as the Japanese landed on Philippine soil. The capital city, Manila, was bombed by enemy planes. So, La Salle, being located at the far end of the city and being far from the city center of Binondo, Ermita and Sta. Cruz, became a center of refuge for civilians.

De La Salle College, 1945. © Manila Nostalgia/Isidra Reyes

A shelled-out balcony of the St. La Salle Hall. © Prof. Xiao Chua

The Battle of Manila devastated and greatly reduced the Pearl of the Orient Seas into rubble. More than eighty (80) percent of the city's structures were either damaged or ruined. For the civilians, the date 12 February 1945 will forever be etched into their memories. It was when twenty-five (25) civilians and sixteen (16) Lasallian brothers were brutally massacred by the fanatical Japanese forces who vowed to fight to the death in the name of the Shōwa Emperor, known by many as Emperor Hirohito.

St. La Salle Hall shortly after the Battle of Manila in 1945. © De La Salle University

After the liberation of the City of Manila, the St. La Salle Hall was in shambles. Its exterior shelled by belligerent forces, and its halls filled with the stench of death coming from the dead bodies massacred by the Imperial Japanese Forces. Shortly after, the surviving Brothers began to put La Salle back on its feet, introducing more programs into its curriculum offerings.

At present, the St. La Salle Hall is now returned into its former glory by demolishing the front structure which housed the Marilen Gaerlan Conservatory. Because of the demolition, the University would now have an additional green breathing space.

St. La Salle Hall at night. The Marilen Gaerlan Conservatory has not yet been demolished at this time. © iBlog La Salle

In its 103 years of existence as one of the premiere universities in the Philippines, the De La Salle University's St. La Salle Hall gives us stories to tell, stories that will forever be etched on its halls. The St. La Salle Hall is a witness to the country's colorful past, from the dark days of war to the liberation of an occupied nation, and will still be a witness to the progress of the nation in the future.

The St. La Salle Hall with the Marilen Gaerlan Conservatory demolished. © Aaron Sumayo

First City National Bank Building

A faithful restoration being made at the First City National Bank Building, now known as the Juan Luna E-Services Building. © Interaksyon

Manila, capital of the Philippines for more than five hundred (500) years, is the seat of the country's political, educational, financial, and religious power. It's status as the country's primate city have earned the reputation of being the 'Most Beautiful City in the Far East' and as the 'Paris of Asia', but all these monikers were taken away after the city was greatly reduced into rubble during the dying days of the Second World War. Almost seventy years have past, and the city is still trying to regain its status as the finest city in the East. Here and there, new developments have been sprucing up, not to mention the priceless aspect called heritage.

The city was once a lively city, with its streets lined with shops and department stores, theaters, banks, and social clubs. In one of these streets, a building called the First City National Bank stood, and still is, standing proudly along the banks of the Pasig River.

Construction of the First City National Bank in the early 1920s. © Manila Nostalgia/Isidra Reyes

The First City National Bank Building is a five-storey office building located along the corner of Calle Juan Luna, formerly Calle Anloague, and Muelle de la Industria in Binondo. One prominent building also stands along the thoroughfare which is the El Hogar Filipino Building. The building, a joint project between the International Banking Corporation and the Pacific Commercial Company, sits on a 1,800 square meter lot and is designed by the architectural firm Murphy, McGill, and Hamlin of New York in the beaux-arts style of architecture. Its design is said to be originated from the management of the International Banking Corporation, with its design coming from the trademark bank design of the company in other overseas branches.

First City National Bank, viewed from the banks of the Pasig River. © Manila Nostalgia/Isidra Reyes

According to University of the Philippines' Prof. Gerard Lico's book entitled 'Arkitekturang Filipino: A History of Architecture and Urbanism in the Philippines', it is stated that the First City National Bank's design was a prototype of the other overseas bank branches.

"The bank’s prototype was made up of a row of colossal columns in antis, which was faithfully reproduced for its Manila headquarters. The ground floor was fully rusticated to effect a textured finish. This floor had arched openings with fanlights emphasized by stones forming the arch. The main doors were adorned with lintels resting on consoles. Above the ground floor were six three-storey high, engaged Ionic columns, ending in an entablature topped by a cornice. These six columns dominating the south and west facades were, in turn, flanked by a pair of pilasters on both fronts. The fifth floor was slightly indented and also topped by an entablature crowned by strip of anthemion." (excerpt from Arkitekturang Filipino: A History of Architecture and Urbanism in the Philippines)

The First City National Bank Building in the 1960s.

The First City National Bank Building survived the horrors of the Battle of Manila in 1945. It was one of the few buildings left almost intact. During the post war years, the building was briefly used as the office of Ayala Life-FGU until they completely moved out to transfer to Makati.

Recently, an interest on the First City National Bank Building was shown after it was bought by a business process outsourcing company to be converted into a call center. The building was renamed as the Juan Luna E-Services Building and is still under restoration. As of this year 2014, the restoration of the building is almost complete and will soon be ready to be leased to its new occupants.

The new Juan Luna E-Services Building currently under careful resotration. © Urban Roamer

Along the scenic Dewey Boulevard, where the pride of the City of Manila, the Manila Bay, is located, there were numerous stately homes and apartments that stood in front of its glowing waters. One of them is the Admiral, located at the corner of Dewey Boulevard and Cortabitarte. The Admiral Apartments had been home to numerous historical figures, both local and global, and had been a witness to the gruesome days of the Second World War.

Admiral Apartments during the post-war years. © Manila Nostalgia/Isidra Reyes

The Admiral Apartments along Dewey Boulevard, now Róxas Boulevard, was a work of the eminent Fernando H. Ocampo, whose other works include the Calvo Building along Escolta, Angela Apartments in Malate, and the post-war rehabilitation of the Manila Cathedral. Built in 1938 and completed in 1939, the Admiral Apartments was commissioned by Don Salvador Araneta Zaragoza and his spouse, Doña Victoria López de Araneta.

Salvador Araneta Zaragoza and Doña Victoria López de Araneta.

The Admiral Apartments, after its opening in the late 1930s, was one of the tallest residential building in the city, with eight storeys high living quarters. Because of its height, the Admiral became the focal point of sailors and ships anchoring in Manila Bay.

Modern-day Admiral Apartments-turned hotel. Ⓒ Manila Nostalgia/Isidra Reyes

According to Manila society legends, the Admiral was conceived by Doña Victoria's mother, Doña Ana López Ledesma. It was said that Doña Ana was responsible for financing the construction of the Admiral to please and impress the Aranetas, specifically Don Salvador's father Don Gregorio Araneta Soriano, because it has been told that Don Salvador had married Doña Victoria without their knowledge.

The Admiral was designed in the art-deco style, designed by the eminent Fernando H. Ocampo. According to an architectural historian, he described the Admiral of having "an air of quiet elegance with definite Spanish touches in the design of its façade. The apartments were pleasant spacious, airy, and bright rooms. The Spanish feeling became more pronounced in the reception room that opened directly to a side street. Both the furniture and the metal chandeliers reflected a Spanish Gothic style, rather forbidding in its formality." (excerpts from a PowerPoint presentation by Isidra Reyes. Retrieved from Manila Nostalgia)

The features of the Admiral's interiors, such as the main dining halls, were designed with different themes and motifs. "The main dining room, called the Malayan Court, was so-called due to the strong Malayan motif of its design and an imposing mural painting by Antonio Dumlao. The Spanish Room was a reception room while a small dining room called the Blue Room was done in royal blue, old rose, crystal, and silver. A cocktail lounge called the Coconut Grove was decorated with a coconut trees with green light bulbs as fruits, inspired by the Cocoanut Grove Nightclub at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles." (excerpts from a PowerPoint presentation by Isidra Reyes. Retrieved from Manila Nostalgia)

During the war, the couple's own home, the Victoneta I, was seized by the Japanese and made it their headquarters. So, the couple and their family moved to the Admiral to seek refuge, along with other members of the López-Araneta families. It has been said that Doña Victoria personally did the washing of the dirty linens and taking phone calls as the Admiral Apartments was understaffed. In the last days of the war, the Japanese took control of the Admiral Apartments. With that, the Araneta couple moved out of the Admiral and sought refuge in Baguio along with other members of the López-Araneta family.

The Admiral Apartments (top center), during the liberation of Manila in 1945.Ⓒ Manila Nostalgia/Andi Desideri

The battle for the liberation of the City of Manila left most of the city in ruins. The Admiral Apartments was not severely damaged in the fight for the recapture of the Philippine capital. Shortly before the capitulation of the Japanese forces in the Philippines, top commanders of Allied nations in the Pacific stayed in the Admiral Apartments. The Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces in the Pacific and Field Marshal of the Philippine Army Douglas MacArthur has made the Admiral his temporary home after his home in nearby Manila Hotel was bombed out during the liberation. The British supreme commander, The Earl Mountbatten of Burma, formerly Prince Louis of Battenberg, uncle of Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, also stayed in the Admiral Apartments.

Construction workers demolish the Admiral Apartments. Ⓒ GMA News/Danny Pata

This year, in 2014, news regarding the Admiral Apartments sparked when it was reported that it is being demolished to pave way for a new development, the Admiral Hotel by Anchor Land Holdings. Petitions have been made throughout social media by heritage conservation activists and ordinary citizens alike, saying that the capital city of Manila has already had too much "massacre" of heritage buildings. The petition for the stopping of the demolition had reached the Manila City Hall, but took a blind eye on the issue. So, the developer, Anchor Land Holdings, continued the demolition, much to the disappointment and frustrations of heritage conservationists.

The year 2014 has already been a roller-coaster ride for Philippine heritage. No concrete plans and actions have been laid out by the government for the protection of heritage structures. As long as there are no concrete and stricter laws regarding the destruction of heritage structures, they will fall prey to greedy developers whose aim is to destroy the country's physical heritage.

A competition for the design of the new school building was initiated by the Lasallian brothers. Tomás Mapúa, a pensionado architect, won the competition against nine other entries and was awarded with a prize of P5,000.00. Mapúa is the country's first registered architect who was one of the first-generation pensionado architects who studied abroad. Educated in Cornell University in New York, he became one of the country's leading architects during the pre-war years, with projects such as the De La Salle University's St. La Salle Hall and the Philippine General Hospital.

The cornerstone for the new school building was laid by the Archbishop of Manila, the Most Reverend Michael J. O'Doherty, in March of 1920. The St. La Salle Hall was completed almost four years after, owing to the phase-by-phase construction because of the Brothers' lack of funds. The new school building was officially opened in December 1924.

St. La Salle Hall in the 1930s. © Easyphil.com

According to an article by Arch. Augusto Villalon on the Philippine Daily Inquirer, the St. La Salle Hall is the only Philippine structure to be included in the coffee-table book 1001 Buildings You Must See Before You Die: The World's Architectural Masterpieces. Denna Jones, one of the book's contributors, Denna Jones, have written about the St. La Salle Hall as an epitome of classical and imperial style of architecture not just in the Philippines but also in Southeast Asia.

"Mapúa's H-shaped, three-story reinforced concrete building is pure Classical expression. A triangular pediment crowns an entablature of cornice, frieze and architrave supported by Corinthian columns to create a three-bay portico main entrance."

"Wide, open-air portico wings extend from either side; the square openings on the third floor balanced over the rectangular openings of the upper floors? balustrade level. Corinthian pilasters and a dentiled cornice unite the floors between each arch."

"The interior quadrangle is similarly ordered but stripped to basic flat elements without benefit of pediment and entablature. A later addition of an exterior green metal slope-roof walkway wraps the ground level on the quadrangle side. The ground floor interior offsets Corinthian grandeur with the geometric simplicity of Tuscan columns, and a square coffered ceiling." (excerpt from Inquirer.net, original text by Denna Jones)

The Chapel of the Most Blessed Sacrament. © Manila Nostalgia/Isidra Reyes

In 1939, an addition was made to the St. La Salle Hall. Mapúa added a chapel on the western-most side of the building. After its completion, it was named as the Chapel of the Most Blessed Sacrament and was dedicated to St. Joseph.

The years 1941 to 1945 were bitter years for the Philippines. The country was unexpectedly and forcibly dragged into war as the Japanese landed on Philippine soil. The capital city, Manila, was bombed by enemy planes. So, La Salle, being located at the far end of the city and being far from the city center of Binondo, Ermita and Sta. Cruz, became a center of refuge for civilians.

De La Salle College, 1945. © Manila Nostalgia/Isidra Reyes

A shelled-out balcony of the St. La Salle Hall. © Prof. Xiao Chua

The Battle of Manila devastated and greatly reduced the Pearl of the Orient Seas into rubble. More than eighty (80) percent of the city's structures were either damaged or ruined. For the civilians, the date 12 February 1945 will forever be etched into their memories. It was when twenty-five (25) civilians and sixteen (16) Lasallian brothers were brutally massacred by the fanatical Japanese forces who vowed to fight to the death in the name of the Shōwa Emperor, known by many as Emperor Hirohito.

St. La Salle Hall shortly after the Battle of Manila in 1945. © De La Salle University

After the liberation of the City of Manila, the St. La Salle Hall was in shambles. Its exterior shelled by belligerent forces, and its halls filled with the stench of death coming from the dead bodies massacred by the Imperial Japanese Forces. Shortly after, the surviving Brothers began to put La Salle back on its feet, introducing more programs into its curriculum offerings.

At present, the St. La Salle Hall is now returned into its former glory by demolishing the front structure which housed the Marilen Gaerlan Conservatory. Because of the demolition, the University would now have an additional green breathing space.

In its 103 years of existence as one of the premiere universities in the Philippines, the De La Salle University's St. La Salle Hall gives us stories to tell, stories that will forever be etched on its halls. The St. La Salle Hall is a witness to the country's colorful past, from the dark days of war to the liberation of an occupied nation, and will still be a witness to the progress of the nation in the future.

At present, the St. La Salle Hall is now returned into its former glory by demolishing the front structure which housed the Marilen Gaerlan Conservatory. Because of the demolition, the University would now have an additional green breathing space.

St. La Salle Hall at night. The Marilen Gaerlan Conservatory has not yet been demolished at this time. © iBlog La Salle

The St. La Salle Hall with the Marilen Gaerlan Conservatory demolished. © Aaron Sumayo

The new Juan Luna E-Services Building currently under careful resotration. © Urban Roamer

University of Santo Tomas Main Building

The University of Santo Tomás Main Building during the pre-war years. © Old Manila Nostalgia via Ram Roy

If there were to be a competition on the best university building anywhere in the Philippines, the best bet would be the University of Santo Tomás in Sampaloc, Manila. Many have bear witness to the building's colorful history. It has gone through the darkest days of war up to the present problems of the university -- flooding. The main building of Santo Tomás has a lot to offer to the community.

The Pontifical and Royal University of Santo Tomás, or UST, is a Catholic university run by the Order of Preachers, or simply known as the Dominicans. It is also the oldest university in Asia, being founded in 1611, even older than Harvard University itself. Many of the Philippines' distinguished men and women have either graduated or have attended at this prestigious university. Heroes like Dr. José P. Rizal, Marcelo H. del Pilar, and Emilio Jacinto; statesmen like Claro M. Recto, Manuel L. Quezón, and Sergio Osmeña have all attended Santo Tomás.

Before being located on its present site, Santo Tomás held its classes inside the walled city in Intramuros, where the old Santo Domingo Church also stood. The university had been wanting to move its operations outside Intramuros because of its ever-increasing student population. The move to a larger site was fulfilled only after three hundred years of being at its Intramuros campus. In 1911, a donation was given to the Dominican Fathers, a 22.1 hectare land located in Sulucan Hills, in the northeastern part of the city. The estate was then a property of the Sisters of Saint Clare, but in the early 1900s, they disposed off the land and sold to developers. One of the buyers, Doña Francisca Bustamante Bayot, donated the land to the Dominicans. The land was bordered by four streets: Calle España, Calle Gov. Forbes, Calle Dapitan, and Calle P. Noval. Because the new campus was more than enough to accomodate its population, the plan was that half of the property was originally intended for Colegio de San Juan de Letrán. However, the plan was not materialized.

Fr. Roque Ruaño, O.P., architect and engineer of the Main Building. © Wikipedia

The university received the donation of the Sulucan property in 1911, the tricentennial anniversary of Santo Tomás. In December of that year, the laying of the first cornerstone was made by the Dominican Fathers, headed by the university's Rector Magnificus Fr. José Noval, O.P., and other distinguished guests.

The development of the new Sulucan property did not materialize until the 1920s due to lack of funds. However, the development of the design had already started. With the development of the new campus went into full swing, the project was handed over to Fr. Roque Ruaño, O.P., a Spanish Dominican who was a former rector of the Colegio de San Juan de Letrán. Ruaño, a civil engineer, had meticulously researched earthquake-proof engineering designs and had tested them when he designed Dominican friar houses in Baguio and Lingayen.

Construction for the Main Building started in 1923. Rebars are being installed, as seen in the photo. © Manila Nostalgia/Prof. Vic Torres

Designed in the Renaissance Revival style of architecture, Fr. Ruaño's design for the Main Building was advanced in its time, as some say it still complies with today's National Building Code. Construction started in 1923, but Fr. Ruaño had already spent the last two years procuring building materials such as cement and rebars from Japan.

"The Sulucan strata consisted of fine sand and loamy clay heavily interspersed with land and marine shells, a situation where the land layers moved at different directions during a tremor. This prompted Fr. Ruaño to combine two methods of laying foundations: Isolated piers were linked with a continuous slab foundation, so that the structures above would sway independently of each other during an earthquake. In five years, 200 workers from Pampanga slowly raised 40 separate small towers that provided the basic framework of what is today?s Main Building (it was called 'New Building' then, there being no other edifice in the campus). Fr. Ruaño kept revising his plans, the latest after a trip to Tokyo in 1926 where he observed the effects of the recent earthquake there and in Yokohama." (excerpt from Inquirer.net)

Construction of the Main Building taking place, circa 1923-1927. © Manila Nostalgia/Prof. Vic Torres

The Main Building has four floors, plus an additional nine-storey clock tower, which contained the water tanks for the hydraulic engineering laboratory. The building is seventy-four (74) meters wide and eighty-six (86) meters long, with two courtyards on each wing. The main engineering feat of the Main Building is that it was built in forty (40) separate structures so that the building would not easily crumble if an earthquake occurs. Also, an additional floor was added to accommodate laboratories.

The Main Building finally opened in time for the 1927-1928 school year. It was a relief for the university administration as they wanted to de-clog its Intramuros campus as fast as possible. After its opening in 1927, the Main Building, specifically the clock tower, served as the city's "Kilometer Zero" until it was replaced by the Rizal Monument in Luneta.

Main Building, circa 1928. © Manila Nostalgia/Lou Gopal

After its opening, the university administration moved some of its operations at Sulucan. The colleges of Philosophy, Pharmacy, Education, Liberal Arts and Medicine held classes inside its halls. The university library also moved in Sulucan, occupying its northeast wing.

Main Building during the 1930s. © Manila Nostalgia/Mon Ancheta

Because of the Main Building's grandeur, it was constructed right at the heart of the twenty-two hectare Sulucan property. It became the focal point of the university, in which the succeeding buildings were all built around it.

Pre-war Santo Tomás came into a halt in 1941 when the Japanese bombed the City of Manila. However, the Japanese occupation of the Philippine capital did not materialize until January of 1942 when the Philippine Commonwealth left Manila for Bataan. For Santo Tomás, war did not spare them from being dragged into occupation. The university was converted into an internment camp, being host to about four thousand Allied and foreign civilian prisoners-of-war, with nationalities such as American, British, Canadian, Australian, Dutch, Pole, Russian, Spanish, Cuban, Mexican, Burmese, Swedish, Danish, and Chinese.

After its establishment in 1942, the Santo Tomás Internment Camp became one of the largest in the Philippines.

Allied and other foreign internees made shantytowns in one of the Main Building's courtyards. © LIFE/Carl Mydans via Discovering the Old Philippines: People, Places, Heroes, Historical Events

An aerial view of the Main Building. Take note of the cramped shanties built in and around the Main Building. © Manila Nostalgia/Mon Ancheta

During the Japanese occupation of Santo Tomás, the university grounds literally became a miniature city. The Japanese had established a government inside, appointing an American named Lemuel Earl Carroll as its head. According to accounts, the internees owed so much to Carroll, stating that his leadership received favorable approval from the internees.

A Japanese propaganda photo depicting life inside Santo Tomás. © Santo Tomas Internment Camp/Lou Gopal

In February of 1945, the combined Filipino and American armies made an assault on the City of Manila. They first took Santo Tomás with the belief that the Japanese will execute all internees as they retreat from the capital. As the American tanks and troops advanced through the campus, they were met by Japanese resistance. The Japanese took the Education Building and held two hundred (200) internees hostage. After negotiations made by a British missionary named Ernest Stanley, the Japanese agreed to leave Santo Tomás and rejoined with other Japanese units in Manila.

The flag of the United States is draped at the canopy of the Main Building, signifying the liberation of the Santo Tomás Internment Camp from the Japanese. © LIFE/Carl Mydans via Wikipedia

The war had left most of the city into rubble. Santo Tomás, however, was not heavily damaged during the liberation as it was still host to a number of Allied war prisoners. After the war, life had returned to normal, students went back to school after a three and a half years hiatus.

University of Santo Tomás Main Building circa 1945. © Flickr/John Tewell

In 1952, during the silver jubilee of the Main Building, an addition to the Main Building was made. Through the initiative of then-Rector Magnificus Fr. Ángel de Blas, O.P., fifteen (15) statues of famous saints, philosophers, and other personalities of the arts and sciences were installed at the pedestals made long before. In the original plan, Fr. Ruaño had purposely built pedestals to put in statues, but it was only made into fruition years after his death. The statues, measuring three meters in height, were sculpted by the great Francesco Riccardo Monti, an Italian expatriate and then-dean of the University of Santo who also made a number of significant works in Manila's buildings such as in the Manila Metropolitan Theater, Capitol Theater, Manila Electric Railroad and Light Company Building along Calle San Marcelino, and the Quezón Memorial.

THE INITIATOR AND THE SCULPTOR: The University's Rector Magnificus, Very Rev. Dr. Fr. Ángel de Blas, O.P. (left), and the master builder Francesco Riccardo Monti (right) © Anna Filippicci

In 2010, a year before the quadricentennial anniversary of the University, the National Museum of the Philippines declared the Main Building, along with other important structures in the University, as National Cultural Treasures.

The Pontifical and Royal University of Santo Tomás, or UST, is a Catholic university run by the Order of Preachers, or simply known as the Dominicans. It is also the oldest university in Asia, being founded in 1611, even older than Harvard University itself. Many of the Philippines' distinguished men and women have either graduated or have attended at this prestigious university. Heroes like Dr. José P. Rizal, Marcelo H. del Pilar, and Emilio Jacinto; statesmen like Claro M. Recto, Manuel L. Quezón, and Sergio Osmeña have all attended Santo Tomás.

Before being located on its present site, Santo Tomás held its classes inside the walled city in Intramuros, where the old Santo Domingo Church also stood. The university had been wanting to move its operations outside Intramuros because of its ever-increasing student population. The move to a larger site was fulfilled only after three hundred years of being at its Intramuros campus. In 1911, a donation was given to the Dominican Fathers, a 22.1 hectare land located in Sulucan Hills, in the northeastern part of the city. The estate was then a property of the Sisters of Saint Clare, but in the early 1900s, they disposed off the land and sold to developers. One of the buyers, Doña Francisca Bustamante Bayot, donated the land to the Dominicans. The land was bordered by four streets: Calle España, Calle Gov. Forbes, Calle Dapitan, and Calle P. Noval. Because the new campus was more than enough to accomodate its population, the plan was that half of the property was originally intended for Colegio de San Juan de Letrán. However, the plan was not materialized.

Fr. Roque Ruaño, O.P., architect and engineer of the Main Building. © Wikipedia

The university received the donation of the Sulucan property in 1911, the tricentennial anniversary of Santo Tomás. In December of that year, the laying of the first cornerstone was made by the Dominican Fathers, headed by the university's Rector Magnificus Fr. José Noval, O.P., and other distinguished guests.

The development of the new Sulucan property did not materialize until the 1920s due to lack of funds. However, the development of the design had already started. With the development of the new campus went into full swing, the project was handed over to Fr. Roque Ruaño, O.P., a Spanish Dominican who was a former rector of the Colegio de San Juan de Letrán. Ruaño, a civil engineer, had meticulously researched earthquake-proof engineering designs and had tested them when he designed Dominican friar houses in Baguio and Lingayen.

Construction for the Main Building started in 1923. Rebars are being installed, as seen in the photo. © Manila Nostalgia/Prof. Vic Torres

Designed in the Renaissance Revival style of architecture, Fr. Ruaño's design for the Main Building was advanced in its time, as some say it still complies with today's National Building Code. Construction started in 1923, but Fr. Ruaño had already spent the last two years procuring building materials such as cement and rebars from Japan.

"The Sulucan strata consisted of fine sand and loamy clay heavily interspersed with land and marine shells, a situation where the land layers moved at different directions during a tremor. This prompted Fr. Ruaño to combine two methods of laying foundations: Isolated piers were linked with a continuous slab foundation, so that the structures above would sway independently of each other during an earthquake. In five years, 200 workers from Pampanga slowly raised 40 separate small towers that provided the basic framework of what is today?s Main Building (it was called 'New Building' then, there being no other edifice in the campus). Fr. Ruaño kept revising his plans, the latest after a trip to Tokyo in 1926 where he observed the effects of the recent earthquake there and in Yokohama." (excerpt from Inquirer.net)

Construction of the Main Building taking place, circa 1923-1927. © Manila Nostalgia/Prof. Vic Torres

The Main Building has four floors, plus an additional nine-storey clock tower, which contained the water tanks for the hydraulic engineering laboratory. The building is seventy-four (74) meters wide and eighty-six (86) meters long, with two courtyards on each wing. The main engineering feat of the Main Building is that it was built in forty (40) separate structures so that the building would not easily crumble if an earthquake occurs. Also, an additional floor was added to accommodate laboratories.

The Main Building finally opened in time for the 1927-1928 school year. It was a relief for the university administration as they wanted to de-clog its Intramuros campus as fast as possible. After its opening in 1927, the Main Building, specifically the clock tower, served as the city's "Kilometer Zero" until it was replaced by the Rizal Monument in Luneta.

Main Building, circa 1928. © Manila Nostalgia/Lou Gopal

After its opening, the university administration moved some of its operations at Sulucan. The colleges of Philosophy, Pharmacy, Education, Liberal Arts and Medicine held classes inside its halls. The university library also moved in Sulucan, occupying its northeast wing.

Main Building during the 1930s. © Manila Nostalgia/Mon Ancheta

Because of the Main Building's grandeur, it was constructed right at the heart of the twenty-two hectare Sulucan property. It became the focal point of the university, in which the succeeding buildings were all built around it.

Pre-war Santo Tomás came into a halt in 1941 when the Japanese bombed the City of Manila. However, the Japanese occupation of the Philippine capital did not materialize until January of 1942 when the Philippine Commonwealth left Manila for Bataan. For Santo Tomás, war did not spare them from being dragged into occupation. The university was converted into an internment camp, being host to about four thousand Allied and foreign civilian prisoners-of-war, with nationalities such as American, British, Canadian, Australian, Dutch, Pole, Russian, Spanish, Cuban, Mexican, Burmese, Swedish, Danish, and Chinese.

After its establishment in 1942, the Santo Tomás Internment Camp became one of the largest in the Philippines.

After its establishment in 1942, the Santo Tomás Internment Camp became one of the largest in the Philippines.

Allied and other foreign internees made shantytowns in one of the Main Building's courtyards. © LIFE/Carl Mydans via Discovering the Old Philippines: People, Places, Heroes, Historical Events

An aerial view of the Main Building. Take note of the cramped shanties built in and around the Main Building. © Manila Nostalgia/Mon Ancheta

During the Japanese occupation of Santo Tomás, the university grounds literally became a miniature city. The Japanese had established a government inside, appointing an American named Lemuel Earl Carroll as its head. According to accounts, the internees owed so much to Carroll, stating that his leadership received favorable approval from the internees.

A Japanese propaganda photo depicting life inside Santo Tomás. © Santo Tomas Internment Camp/Lou Gopal

In February of 1945, the combined Filipino and American armies made an assault on the City of Manila. They first took Santo Tomás with the belief that the Japanese will execute all internees as they retreat from the capital. As the American tanks and troops advanced through the campus, they were met by Japanese resistance. The Japanese took the Education Building and held two hundred (200) internees hostage. After negotiations made by a British missionary named Ernest Stanley, the Japanese agreed to leave Santo Tomás and rejoined with other Japanese units in Manila.

The flag of the United States is draped at the canopy of the Main Building, signifying the liberation of the Santo Tomás Internment Camp from the Japanese. © LIFE/Carl Mydans via Wikipedia

The war had left most of the city into rubble. Santo Tomás, however, was not heavily damaged during the liberation as it was still host to a number of Allied war prisoners. After the war, life had returned to normal, students went back to school after a three and a half years hiatus.

University of Santo Tomás Main Building circa 1945. © Flickr/John Tewell

In 1952, during the silver jubilee of the Main Building, an addition to the Main Building was made. Through the initiative of then-Rector Magnificus Fr. Ángel de Blas, O.P., fifteen (15) statues of famous saints, philosophers, and other personalities of the arts and sciences were installed at the pedestals made long before. In the original plan, Fr. Ruaño had purposely built pedestals to put in statues, but it was only made into fruition years after his death. The statues, measuring three meters in height, were sculpted by the great Francesco Riccardo Monti, an Italian expatriate and then-dean of the University of Santo who also made a number of significant works in Manila's buildings such as in the Manila Metropolitan Theater, Capitol Theater, Manila Electric Railroad and Light Company Building along Calle San Marcelino, and the Quezón Memorial.

THE INITIATOR AND THE SCULPTOR: The University's Rector Magnificus, Very Rev. Dr. Fr. Ángel de Blas, O.P. (left), and the master builder Francesco Riccardo Monti (right) © Anna Filippicci

In 2010, a year before the quadricentennial anniversary of the University, the National Museum of the Philippines declared the Main Building, along with other important structures in the University, as National Cultural Treasures.

Ideal Theater

Ideal Theater during its pre-war heyday. Ⓒ Manila Nostalgia/Isidra Reyes

Manila was a city which served as a model of pre-war prosperity. Its other Far Eastern neighbors such as Singapore and Hong Kong were no match to Manila's outstanding beauty. The city boasted the finest shops, restaurants, theaters, and institutions that made it earn the title 'Most Beautiful City in the Far East'. Along the fabulous Avenida de Rizal, known to many as the Avenida, there are numerous theaters to choose from. One of these theaters was the Ideal, considered by Manila's alta sociedad as one of the best theaters in the city.

The Ideal Theater was an art-deco masterpiece designed by the National Artist for Architecture Pablo Antonio in 1933. The theater, owned by the Roces family, in partnership with Teotico, Basa, Tuason, and Guidote families, has been operating since 1912, with the first theater made out of wood.

Pablo Antonio y Sebero, architect of the Ideal Theater. Ⓒ History of Architecture

As mentioned, the Ideal Theater was commissioned by the Roces family to Pablo Antonio, one of the second-generation Filipino architects who came back after studying or training overseas. Antonio's commission on the Ideal made an impact to his career. Later on, he would design other Manila landmarks, such as the Far Eastern University, White Cross Orphanage, and the post-war Manila Polo Club in Forbes Park.

The Ideal was then the exclusive exhibitors of MGM motion picture films in the Philippines. Ⓒ Paulo Alcazaren

The Ideal projected an art-deco style of architecture. This type of architectural style was prevalent in the 1930s, wherein cinemas and theaters were designed using this style. One of its interesting features is that it boasted a streamline design -- that is, it was adorned with smooth curves and finishes. After its completion in 1933, the Ideal became one of the city's best theaters. Because of its location along the Avenida de Rizal, many theaters soon rose on its grounds. Rival theaters such as the State, Ever, and Avenue owned by the Rufino family built their theaters along Avenida de Rizal.

The Ideal (center), and the Roces Building (left), taken sometime in the late 1930s. Ⓒ Manila Nostalgia/Isidra Reyes

Ideal Theater's proscenium. Take note of the streamline design of the arches. Ⓒ Manila Nostalgia/Isidra Reyes

During the Japanese occupation, the Ideal, along with other theaters in the city did not feature Hollywood films, but instead showed Japanese films and stage plays used for propaganda.

The liberation of the City of Manila in February of 1945 brought great suffering to hundreds of thousands of innocent civilians. More than fifty percent of the structures in the city were either damaged or completely ruined. The Ideal was one of the structures in the city that was not totally devastated during the month-long battle.

Post-war rehabilitation came immediately after 1945. Many of the city's destroyed structures were either rebuilt or completely demolished to pave way to new and modern structures. The Ideal was rebuilt, along with other movie theaters in the city. In fact, movie theaters were the first to be rebuilt as many people demanded entertainment.

The emergence of air-conditioned shopping malls such as Quad and ShoeMart paved way to the decline of the standalone movie theaters. In the case of the Ideal, and other theaters located along the Avenida, it was due to the construction of the elevated Light Rail Transit in the 1980s.

The Ideal, once the gem of Rizal Avenue's theaters, closed down in the 1970s and was demolished to make way for shopping arcade.

La Insular Cigar and Cigarette Factory

The Insular Cigar and Cigarette Factory in Binondo. © Arkitekturang Filipino via Pinterest

Pre-war Manila was a haven for architectural beauty. Structures dating from the 16th century Spanish architecture up to the 20th century American style architecture, Manila had it all. The city's numerous edifices made it as the 'Paris of Asia', and the 'Most Beautiful City in the Far East'. But all that monikers were taken away when the city was wiped out during the dying days of World War II. Since then, Manila has never regained its status as the finest city in the Orient.

On the northern part of the city lies Binondo, considered as the city's business district and home to the world's oldest Chinatown. One of the most imposing structures one can find during the pre-war years was located in this part of the city, the La Insular Cigar and Cigarette Factory.

Two imposing structures adorn the Plaza Calderón de la Barca, the Hotel de Oriente (left), and the La Insular Cigar and Cigarette Factory (right). © Lougopal.com/Manila Nostalgia

The La Insular Cigar and Cigarette Factory was a three-storey, Neo-Mudéjar structure located along on the right of Binondo Church along the Plaza Calderón de la Barca. Like its neighbor, the Hotel de Oriente, the La Insular was also designed by Spanish architect Juan José Hervas Arizmendi, under the command of its owners, Don Joaquín Santamarina and Don Luis Elizalde.

Note: Names are written in standard Spanish naming custom. Spanish names are written without the Filipino 'y'. So, for males (or single females), it would be [given name][paternal family name][maternal family name]. For married females, it would be [given name][paternal family name][maternal family name]de[husband's family name]. For widows, it would be [given name][paternal family name][maternal family name]vda.de[husband's family name].

Juan José Hervas Arizmendi, architect of the imposing La Insular Cigar and Cigarette Factory. © Manila Nostalgia/Paulo Rubio

The La Insular was established sometime in the 1880s after the abolition of the tobacco monopoly by the Spanish colonial government in the Philippines. Its owners, Don Joaquín Santamarina, Don Luis Elizalde, and their associates formed the La Insular Tobacco as a result.

La Insular Cigar and Cigarette Factory. Photo taken from the Plaza Calderón de la Barca in front of the Hotel de Oriente. The Binondo Church can also be seen in the background. © Skyscrapercity.com via Manila Nostalgia

One of the most distinguishing features of the La Insular was its neo-mudéjar style of architecture. Only a few structures in the city were designed in the neo-mudéjar style, one being the former Augustinian Provincial House in Intramuros. The La Insular stood out from the rest of the structures located along the plaza due to its tall archways and projecting balconies, which were adorned with intricate lampposts. In its interior, the La Insular sported a broad staircase and a courtyard.

A wiped-out Manila in aerial view. The La Insular`s ruins is nowhere to be found as it was completely consumed by fire in 1944. © Flickr/John Tewell via Skyscrapercity.com

In 1944, a fire destroyed the beautiful La Insular cigarette factory. It was never again rebuilt due to the liberation of Manila in 1945.

Note: Names are written in standard Spanish naming custom. Spanish names are written without the Filipino 'y'. So, for males (or single females), it would be [given name][paternal family name][maternal family name]. For married females, it would be [given name][paternal family name][maternal family name]de[husband's family name]. For widows, it would be [given name][paternal family name][maternal family name]vda.de[husband's family name].

Juan José Hervas Arizmendi, architect of the imposing La Insular Cigar and Cigarette Factory. © Manila Nostalgia/Paulo Rubio

The La Insular was established sometime in the 1880s after the abolition of the tobacco monopoly by the Spanish colonial government in the Philippines. Its owners, Don Joaquín Santamarina, Don Luis Elizalde, and their associates formed the La Insular Tobacco as a result.

El Hogar Filipino Building

The El Hogar Filipino, one of the city's oldest American era structures, now on the verge of destruction. © Historic Preservation Journal

'Every building has its own story'. Yes, everything, from people to buildings, each has its own story to tell. Structures, though they are non-humans, have also experienced what humans had experienced, such as wars, revolutions, calamities, etc. Buildings, especially old ones, are reminders of a particular era that they were in. So, they are meant to be preserved as they are our physical gateway to the past. The City of Manila boasts many structures that tell stories, many of which have seen the capital transform from an ever loyal Spanish city, to a vibrant American Pearl of the Orient Seas, and to a colorful yet chaotic capital of the Philippine Republic.

The El Hogar Filipino Building is one of those structures that tell stories of the past. The building has seen numerous events, from the American insular government to the Philippine Commonwealth, from the Second Philippine Republic to the liberation of the city, and finally the independence of the country in 1946.

An old colored photo, probably a postcard, of the El Hogar Filipino Building. © Manila Nostalgia/Isidra Reyes

The El Hogar, known in Spanish as the Edificio El Hogar Filipino, is a five-storey office building designed in the beaux-arts/renaissance/neo-classical styles of architecture. Located along Calle Muelle dela Industria by the Pasig River, the El Hogar is flanked by the First City National Building on the right, and the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank Building on its rear and was designed by Spanish-Filipino engineer Don Ramón José de Irureta-Goyena Rodríguez. The El Hogar was built sometime between 1911 and 1914, which it was said to be a wedding present in celebration of the marriage of Doña Margarita Zóbel y de Ayala, sister of patriarch Don Enrique Zóbel y de Ayala, and Don Antonio Melián Pavía, a Spanish businessman who was titled as the Conde de Peracamps.

Don Ramón José de Irureta-Goyena Rodríguez, architect of the El Hogar Filipino. © Manila Nostalgia/Paquito dela Cruz

Don Antonio Melián Pavía, el Conde de Peracamps, and owner of the El Hogar Filipino. © Manila Nostalgia/Paquito dela Cruz

The El Hogar Filipino was owned by Spanish businessman and Conde de Peracamps, Don Antonio Melián Pavía. According to the Cornejo's Commonwealth Directory, Melián was born in the Canary Islands in Spain on May 21, 1879. From Spain, he sailed to Peru in 1903 where he held posts in the insurance company La Previsora and in the Casino Español de Lima. In 1907, he married Don Enrique In 1910, he sailed from Peru to the Philippines and established the El Hogar Filipino and the Filipinas Compañía de Seguros together with his brothers-in-law Enrique and Fernando Zóbel y de Ayala.

Note: Names are written in standard Spanish naming custom. Spanish names are written without the Filipino 'y'. So, for males (or single females), it would be [given name][paternal family name][maternal family name]. For married females, it would be [given name][paternal family name][maternal family name]de[husband's family name]. For widows, it would be [given name][paternal family name][maternal family name]vda.de[husband's family name]

A group photo of the El Hogar Filipino leaders and employees. The Conde de Peracamps is seated at the center, with Don Enrique Zóbel y de Ayala (seated, fourth from right), and his brother Don Fernando Zóbel y de Ayala (seated, third from right). The description reads: Sr. Melián, with the directors and employees of El Hogar Filipino whose company was founded by the said gentleman. © Manila Nostalgia/Paquito dela Cruz

The El Hogar (left), and the First City National Bank Building (right) viewed from the other side of the Pasig River. © Manila Nostalgia/Ingrid Donahue via Lou Gopal

The El Hogar housed the Melián business empire, such as the Filipinas Compañía de Seguros, Tondo de Beneficiencia, Casa de España, Casa de Pensiones, and El Hogar Filipino. Other tenants of the El Hogar include Ayala y Compañía, and Smith, Bell and Company. The Filipinas Compañía de Seguros moved out of the El Hogar in the 1920s after the completion of its own building at the foot of the Jones Bridge in Plaza Moraga, a short walk from the El Hogar.

The El Hogar during the 1920s. © Philippine History and Architecture

One of the building's interesting features is that the building has its own garden courtyards, not one, but two. Another feature that make the El Hogar unique was its mirador, or balcony. From the El Hogar's balcony, one can see the Pasig River, the southern part of Manila, which includes the walled city of Intramuros, Ermita, and Malate. Also, the El Hogar's staircase is considered as one of the most ornate in the city, with a sculpted merlion, a symbol of the City of Manila, as its base.

The El Hogar's intricate staircase grillwork, which included a sculpture of a merlion, a symbol of the City of Manila. © Manila Nostalgia/Isidra Reyes

A memorial plaque in which encases the El Hogar's time capsule. The plaque reads: Excmo. Sr. Don Antonio Melián y Pavía, Conde de Peracamps. Funadador de 'El Hogar Filipino' 1911. It has been reported that the plaque has been removed, and so as the time capsule. © Manila Nostalgia/Stephen John Pamorada