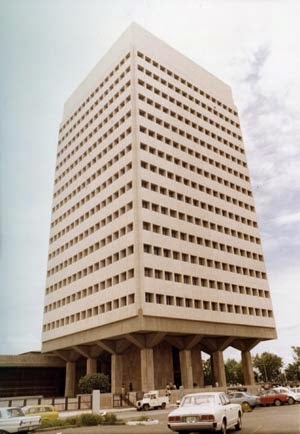

The Ramon Magsaysay Center during the 80s. © Ramon Magsaysay Award Foundation

The Ramón Magsaysay Center is an eighteen-storey edifice built in honor of Philippine President Ramón Magsaysay, who died in a plane crash in Cebu in 1957. The brutalist edifice is located at Roxas Boulevard facing the famous Manila Bay and its sunset. The center currently houses the Asian Library and the offices of the Ramón Magsaysay Award Foundation, the governing body of the Ramón Magsaysay Award, Asia's Nobel Prize.

The RM Center during the 1970s. Viewed from Roxas Boulevard. Note that the Silahis International Hotel/Grand Boulevard Hotel is in its construction progress. © Flickr/rubiopr27

Built in 1967 at the corner of Roxas Boulevard and Dr. Joaquin Y. Quintos St., the Ramon Magsaysay Center was designed by Arturo J. Luz & Associates, in consultation with Italian-American Pietro Belluschi and Alfred Yee Associates, both from the United States and pioneers in designing pre-cast and pre-stressed concrete building structures.

The Ramon Magsaysay Center was the first structure in the country to sport column-free structural concept. The design used pre-cast and pre-stressed beams like a tree rooted on the ground. © Arkitekturang Filipino

That early, the building designers decided to adopt the use of a novel structural system -- the pre-cast, pre-stressed concrete beams and multiple in-place floor slabs and wall panels. The main column of the building is the cast-in-place concrete shear wall core (Moment Frame) over deep concrete piles. This structural system is resistant to lateral forces due to earthquakes or wind load. In effect, the building is designed like a big tree with the columns as its deep-rooted trunk that sways with the wind and the movement of the ground. For elegance and engineering integrity, secondary pillars were installed all covered with travertine cladding.

Ramón Magsaysay Center viewed from below. © That Happy Day

The center's pre-cast and pre-stressed concrete beams which acts like a trunk rooted on the ground. © Urban Roamer

A statue of President Magsaysay placed on the lobby of the building. © Maspaborito.com

The credo of President Magsaysay. © Urban Roamer

The exterior of the Ramón Magsaysay Center was designed to withstand the salty environment that surrounds the building. It was clad with travertine marble slabs embedded in the frame of the building. These types of materials require minimal maintenance but still gives an elegant view of the building.

.jpg)